Single News

Reading in the book of the world – 400 years of Rosicrucian writings

KASSEL (NNA) – Four hundred years ago Landgrave Moritz in Kassel published a couple of small books: the manifestos of the Fraternity of Rosicrucians. They triggered violent controversy across Europe and its followers were persecuted as heretics.

A small R.C. in the corner of a document, the fingers represented in an unusual pose by the artist in a painting – these were the hidden signs with which the members of the Fraternity identified themselves to each other. For the greatest secrecy was one of the basic principles of their order. Research, helping and healing were their goals.

About 100 people had gathered at the end of February to attend the conference “Changing the world under the Rose Cross” which was organised by the Anthroposophical Society in Kassel to investigate further the secrets in the writings Fama Fraternitatis (1614) and Confessio Fraternitatis (1615).

Before the Rosicrucian manifestos were published by Landgrave Moritz of Kassel (1572-1632), they had already been distributed in handwritten form. Indeed, the cover sheet of the Fama contains an indication of the consequences which could arise for readers at the start of the seventeenth century involving themselves with these writings: a Tirolean Rosicrucian, Adam Haselmayer, is mentioned whose positive inclination towards the Fama led to imprisonment and four years’ labour on a galley. No stream in history had been as radically fought against as the Rosicrucians, writes the author Bastian Baan.

“Spiritual thunderbolt”

But why did these small books – ten by fifteen centimetres in size – represent such a threat to the ruling circles and why did Landgrave Moritz print them? The two writings had acted like a “spiritual thunderbolt” said Prof. Ludolf von Mackensen in his lecture at the conference. The manifestos had been translated into five languages. They spread because they brought to expression a general discomfort with the cultural, spiritual and political situation in Europe for which above all the rule of the Catholic Habsburg Monarchy was made responsible.

This was countered by the Rosicrucians with their demand of a “general reformation”. What had been done by Martin Luther in the realm of the Church with his Theses and Reformation was now to be extended to the whole of life. But the “General reformation of the whole wide world”, as set out in the Fama and Confessio, had one particular characteristic: it included the renewal of human beings themselves. The Rose Cross, Rudolf Steiner writes, represented in symbolic form the death of the “lower” and the resurrection of the “higher”. The third work of the Rosicrucians, the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz, printed for the first time in Strasbourg in 1616, documents the intricate inner path of spiritual experience.

In contrast to Christian mystics such as Jakob Böhme, the Rosicrucians decided to turn their eye first outwards to nature and then into their own interior. The “alchemist” wanted to see the “human spiritual being” with the cognitive forces which had been acquired in the “spiritual realm of nature”, as Rudolf Steiner puts it.

Christian Rosenkreuz

The author of the three works is thought to be the Swabian theologian Johann Valentin Andreae. In later life he distanced himself from them and spoke of them as a “ludibrium”, a kind of youthful mistake from his student days. The Fama deals above all with the life and path of knowledge of Christian Rosenkreuz who founded the secret fraternity at the start of the fifteenth century. As a young man he reached the Orient where he became acquainted with the wisdom of Arab scholars. At the gates of Damascus he had an encounter with Christ similar to that of St Paul.

In Damcar, in what is Yemen today, he found a special book, the liber m., which he translated from the Arabic. Roskenkreuz worked on the book with other members of the order; the m. is interpreted as meaning “mundi”, in other words the book of the world – or knowledge of the world as Gerhard Wehr put it. The members of the order decided to work in the outside world, for example through giving selfless and free care to the sick. All this happened in secret until – as the Fama reports – Rosenkreuz’s tomb was discovered 120 years later by members of the order. His body had been “intact and without decomposition”. Gerhard Wehr argued that in this way the Fama highlighted the “spiritual presence of Christian Rosenkreuz”. The inscription on the door of the tomb, “Jesus mihi omia” (Jesus is everything to me), indicated the connection of Rosenkreuz with a universal Christianity.

Understanding the cosmos “from out of heaven” became the public signature of the Fraternity, whose members however continue to work in secret. The subject is a difficult one for historical research looking for sources of Rosicrucian activity since there are no conventional documents or anything of a similar kind, as was repeatedly emphasised during the conference. The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) then completely obliterated any of their extant traces in Europe.

Finding traces

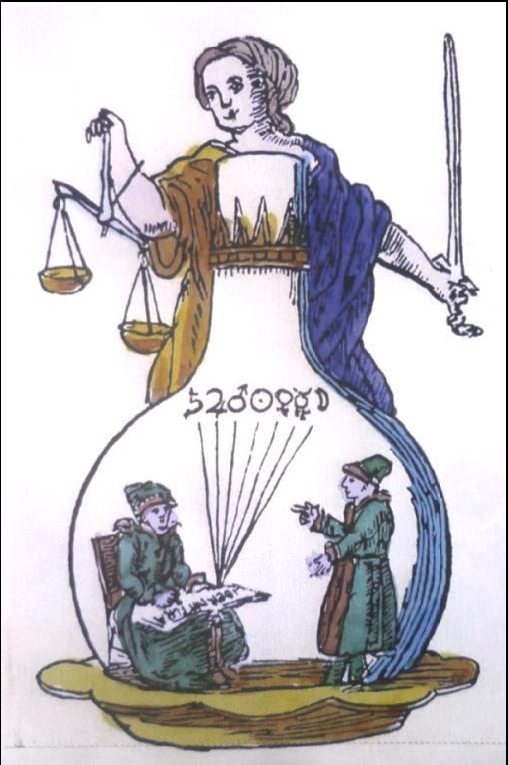

What, then, were the possibilities offered by the conference to study the Fraternity – beyond the manifestos? Here the observation of images with some connection to the Rosicrucians offered an opportunity to dip into the world of their symbols. The objects of such observation were, for example, the secret Rosicrucian figures by Henricus Madathanus of 1785, a painted table top by Martin Schaffner from 1533 and works by Dürer and Rembrandt were also looked at to find Rosicrucian traces. One working group studied the work “Atalanta Fugiens” by Michael Maier, an important alchemist of the time who – coming from the court of Rudolf II in Prague – was the personal physician of Landgrave Moritz.

Dr. Rainer Werthmann looked with a chemist’s eye at the alchemical copper engravings in Maier’s book and decoded them together with the participants as the pictorial representation of chemical processes. The search of the alchemists for the philosopher’s stone and the creation of gold, it was explained in this context, had been more of a byproduct of their activity, their real focus had been on gaining an understanding of nature. In the Confessio the Fraternity also distanced itself from such pseudo alchemy which was only concerned with material gain. The Roscuricans were meant to work without payment.

Freethinking genius loci

The Kassel conference also made clear that it was a special point in human history at which Landgrave Moritz made these Rosicrucian writings public. The new world view as it was set out by Kepler, Galilei or Tycho Brahe was opposed in the Counter-Reformation by strong forces of the Catholic Church and traditional science. Rolf Speckner in his lecture described the fate of Trajano Boccalini whose socially critical satire Ragguali di Parnaso was published together with the manifestos. Although he had settled in Venice where free thought and writing were still possible, he died a violent death there in 1613.

Landgrave Moritz had taken the “spiritual impact” of the new age seriously, Prof. Ludolf von Mackensen emphasised. Indeed, the former director of the Museum of Astronomy and History of Technology in Kassel saw a freethinking genius loci at work in the region of Kassel where, among others, the Brothers Grimm had been at work and which in the eighteenth century had taken in Huguenot refugees fleeing from religious persecution in France. Moritz – who was given the epithet “the scholar” by his contemporaries – collected alchemical writings and there are a series of indications that he played a leading role in the secret Rosicrucian movement.

Inner transformation

The last part of the conference then – in accordance with the world view of the Rosicrucians – dealt with inner transformation. Put in the mood by the works of Jean Sibelius and Arvo Pärt, the participants had the opportunity of meditative practice guided by Thomas Mayer and Agnes Hardorp. Mayer pointed out that Steiner had used the concept of ‘Rosicrucian meditation’ at the beginning of his own work and teachings, but that later this reference to ‘Rosicrucian meditation’ – not the meditative work itself – had disappeared from his work, possibly because Steiner did not wish for people to connect back to events in the past so much when working with such meditative practices.

The special nature of this kind of meditating consisted of the fact that it was determined by waking consciousness. In addition, Steiner proceeded from the possibility of supersensory perception which opened up to a person through meditation. Reading in the book of the world – as a path of meditation in the western and European tradition – is a common feature of anthroposophy and Rosicrucianism. The founder of the Fraternity, Christian Rosenkreuz, could be seen as a kind of guardian of this western path, the conference concluded.

END/nna/ung/cva

Item: 150410-01EN Date: 10 April 2015

Copyright 2015 News Network Anthroposophy Limited. All rights reserved.