Nachrichtenbeitrag

The new biography of Steiner: real portrait or hagiography?

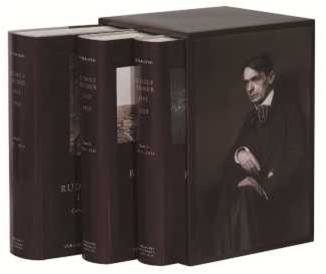

In celebration of the recent 150th anniversary of Rudolf Steiner’s birth, well-known author Peter Selg has published a biography of the founder of anthroposophy. It is certainly a “magnum opus” – three volumes coming in at around 2000 pages – and contains new documentary material that sheds light on the last months of Steiner’s life. There has been a mixed response to the book in reviews published in various anthroposophical journals, as NNA correspondent Wolfgang G. Voegele, writes.

MAINZ (NNA) – In his review in the March isue of Info3 magazine, Ramon Bruell considers the new Steiner biography to be “retrograde”. His article is headed “Steiner on a pedestal”. Bruell thinks that Selg’s biography is an attempt to restore the aura of sanctity to Steiner: “The Doctor has been replaced on the plinth where Selg believes he belongs.”

Bruell believes that anthroposophists who have always regarded Steiner as infallible, and his work and life as perfect and entirely beyond reproach, will rejoice at the publication of these three volumes. But in his view there is no place in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for sainthood in modern culture, science and serious academic discourse. No credence will be given to someone presented in this way. Bruell thinks that publication of this hagiography will discredit Selg as a rigorous academic. Still worse, it may harm public acceptance and acknowledgement of Rudolf Steiner.

Issues of contemporary concern are not raised, let alone answered in these volumes, states Bruell – such as Steiner’s comments on certain ethnic groups, including the Jewish race, which can appear discriminatory to us today. The author has discretely navigated around every possible pitfall that might tarnish the idealized image of Steiner or, in Selg’s words, the “inner continuity of an incomparable life’s work”. Part and parcel of this policy of avoidance is the lack of any mention either of “Rudolf Steiner’s puzzling marriage to his landlady Anna Eunike” and their subsequent alienation from each other when Steiner allied himself with thesosophical circles, and in particular with Marie von Sivers.

The reviewer also pinpoints what he regards as technical errors in the biography: “There is no index of names; the contents page is extremely general and therefore unhelpful to readers who wish to home in on particular aspects of Steiner’s life”. Rather than a bibliography, there is merely a list of the volumes of Rudolf Steiner’s Collected Works (GA). As such, the biography does not even meet ordinary academic standards, and fails to engage with modern discourse on the importance of anthroposophy’s founder. Selg, says Bruell in conclusion, has not “furthered the anthroposophical movement and consolidated its future”, but in fact has done it a “disservice”.

By contrast, Lorenzo Ravagli in his “anthroblog” (March 2013) praises Selg’s “magnum opus”, agreeing with Selg that it was high time to counter the “distorted images” of Steiner in biographies by Helmut Zander, Heiner Ulrich and Marion Gebhardt, released by mainstream publishers to mark the Steiner anniversary year. In his view, the book is a history of Steiner’s life and work that does justice to his stature and spiritual journey.

In particular, Ravagli takes this opportunity to turn some heavy rhetorical guns on the biographer Zander, describing his book as a “botched pseudohistorical effort” and the “epitome of unphilosophy”. Zander has, he says, concealed the fact that his biography is “void of content” by penning “populist trash and disparagement”. In Ravagli’s view, Selg’s subtle perceptions of Rudolf Steiner are a remedy to heal Zander’s “pathology”. He sees Steiner’s life as a battle against the old powers of darkness which sought to extinguish his Christ-centred movement. Ravagli speaks of an “unholy alliance” of ecclesiastical, nationalist and leftwing circles against this movement, which “was capable of preventing” the decline of western culture. Ravagli’s conclusion is couched in superlative terms: Steiner’s life and work, he says, “will endure to the end of time” because, in a way “exemplary to all of us”, it draws on the power of the Resurrected Christ.

In the journal Europäer (March 2013, p. 26 ff.), Franz-Juergen Roemmeler finds that the biography oscillates “between passages of brilliance (…) and others in sore need of more interpretative depth”. Selg’s book, he says, has great breadth of scope rather than profundity. It is a speciality of Selg’s, says Roemmeler, to “link together lengthy citations by different authors”. But the reviewer is put off by the fact that in characterizing the situation in Central Europe, Selg quotes authors – such as Eric Hobsbawn and Klaus Hornung – who are either paid-up communists or “on the far-right margins of political discourse”.

In line with the thematic emphasis of many articles in the Europäer, Roemmeler gives detailed attention to Selg’s chapter on the First World War. Here, he says, Selg draws on some dubious sources, for instance misappropriating important citations from studies by Europäer author Thomas Meyer on Hellmuth von Moltke. Selg, he says, has ommitted to clearly identify the vested interests – anglo-American secret societies – who masterminded the Great War, as Steiner had made clear in his observations on contemporary history.

Selg, says Roemmeler, repeatedly focuses on “the way anthroposophists related to Steiner”. Here the reviewer points to “inner conflicts” that still surface to this day and are also discussed as an ongoing danger in publications such as the Europäer. In this context, Roemmeler is surprised that the further course of events after Steiner’s death in 1925 is left out of the picture. He also doubts whether a mere compilation of quotations is enough to deal with some of these issues in depth. Selg, he says, offers nothing really new, but instead just countless quotations from others. Roemmeler also finds fault with the look of the book: eccentric layout, lack of clear sections, no subtitle, no index of names, places or subjects, no chronology table and confusing footnotes. All of this, he says, makes it harder to follow the text and is likely to put people off buying what is, after all, an expensive book.

In his article in the weekly magazine Das Goetheanum (no. 11/16.3.2013), Wolf Ulrich Kluenker expressly declines to write a “review”, since Selg’s work is “an attempt to erect a monument”. It is the role of a monument, says Kluenker, to speak to our feelings, and the only suitable response therefore is to offer one’s aesthetic impressions.

Kluenker asks, very critically: “Does one really do justice to an individual by enumerating and accentuating his past superlative spiritual and human qualities?” Even Steiner, he goes on, was not incapable of errors and failings. But the blame for this cannot only be ascribed – as Selg ascribes it – to antagonistic surroundings and lack of understanding in Steiner’s colleagues. Is there not a danger, asks Kluenker, “in karmically ossifying Steiner today in the conditions of a different past, thus precluding him and anthroposophy from a viable future?”

Besides criticising external aspects such as the book’s typeface and printing, he finds fault with the frequent “sequences of interlaced quotations” extending over several pages. The author does not shape this material actively enough, he says. In general he sees the biography as burdened by Selg’s aim of imposing his own enthusiasm for Steiner on the reader. The latter can come away rather stultified by this experience, and by the lofty moral claims made upon him.

Kluenker is less bothered by the lack of indexes. Nor are tone and theme something, he thinks, that should be “dictated by one’s opponents”. But Kluenker finds in Selg – as Bruell does – a tendency to obfuscation. Selg is guilty of this, he thinks, in “concealing” the problem of Steiner’s first marriage by attending instead to the spiritual significance of the figure of Anna Eunike’s first husband. He also finds Selg’s account of the Curative Education Course to be too colourless. Its roots in Steiner’s relationship with Pauline and Otto Specht could have been traced and elaborated more clearly – instead of which, unnecessarily according to Kluenker, Selg has reproduced a whole Whitsun lecture by Steiner.

But he finds value in Selg’s account of the last months of Steiner’s life, and the publication of previously unknown documents relating to this period. Here a spiritual dimension becomes visible in human terms. And it is here too that, in his view, the urgent question of a “new human and spiritual impetus” arises for us today.

Guenter Roeschert reviews Selg’s biography in Die Drei (June 2013), and likewise regrets formal deficiencies of the book: lack of subsections and subheadings, the bibliography limited to GA volumes only, and the lack of indexes.

Roeschert believes that Selg’s biography should be seen in the context of his activities in the Anthroposophical Society over recent years. Over the past decade he has been criticizing current aspects of the work of the Society as a failure to honour Steiner’s intentions; and in this work he accentuates that line of argument. It is not accidental that he refers in several passages to Schiller’s “Maltese” fragment where the chorus of older knights invoke the order’s origins, thus uniting the two disputing sides. Selg clearly sees himself in a similar role. The book contains many unsubstantiated assertions, and some real biographical issues in Steiner’s life are just glossed over.

In relation to the question of Christ in Steiner’s life, Selg does not accept there was ever any radical reappraisal. Roeschert thinks that “by employing a method of whitewash, sugar-coating and silence […] Selg offends against truth and the real facts” (p. 71). Selg simply does not “manage to engage” with Steiner’s hostile comments about Christianity, says Roeschert.

Instead, he pursues the “model of an ‘initiate’s’ linear development”. Here the reviewer points to the apostle Paul and his experience of conversion. “Whoever seeks,” he says, “to mask anything negative in Steiner’s life because of a boundless reverence for the man, detaches Steiner’s life from reality” (p. 71). Roeschert does, however, give all dues to the book’s conclusion with its “moving description of the last months of Rudolf Steiner’s life. Here Selg improves upon the detail of Christoph Lindenberg’s account in his two-volume biography of 1997” (p.72).

Roeschert’s summary is, however, sobering: Selg’s book is “not the outcome of genuine biographical research” – which involves the author’s personal view of his subject yet must also aspire to objectivity – but instead a polemical work. “The three volumes are a lengthy appeal to relaunch the anthroposophical project.” Though Roeschert concedes that the situation in which today’s Anthroposophical Society finds itself has not met Steiner’s wide-ranging expectations, he asks nevertheless whether the circumstances really justify Selg’s “call to arms dressed up as a biography”. Ought one to use Steiner’s life in this way, as an instrument for restoring a supposed status quo within the Society?

A summary of the reviews makes clear that Selg’s book does not engage with Steiner critics but is addressed expressly to insiders. Intentionally departing from academic standards, and hard to read, the work is very unlikely to make headway in the public domain. Mainstream critics will find in Selg’s book a confirmation that anthroposophy is a substitute religion rather than a mode of rigorous enquiry.

END/nna/vog/ung/mb

Publication details: Peter Selg: Rudolf Steiner 1861-1925. Lebens-und Werkgeschichte. 3 volumes. 2148 pages, 220 plates. Arlesheim: Verlag des Ita Wegman Instituts, 2012. CHF 210; EUR 169. Each volume is available separately. A translation is in preparation.

Item: 130713-01EN Date: 13 July 2013

Copyright 2013 News Network Anthroposophy Limited. All rights reserved.